The navigation technology that lives in our smartphones and dashboards might seem young, but is the crystal of centuries of exploration and cartography, technical tinkering and commercial competition. Today, they’re background characters in our busy lives — obedient, omniscient friends who always know the best route. And we’re not even done. Navigation continues to be developed by market winds, such as customization. This article plots the rise of in-car navigation; from novelty invention to ubiquity.

Analogue to digital, fixed to portable

100 years ago, motoring was a novel but jagged experience. Streets were often poorly signposted and barely lit. Against this backdrop, early inventions like the Jones Live Map and Baldwin Auto Guide represented a quirky lunge into modernity. These used simple rotary technology to feed directions to the driver. The best documented example is the Iter Avto device, into which the driver would load scrolls depicting fixed routes. With moving paper, glass lenses and brass housing, these systems carried a certain post-Victorian quaintness.

The Iter Avto. Photograph copyright of London Media

Fast-forward a half century to the 1980s, when digital modernity began dripping into consumer homes and cars. Enter Honda Electro Gyro-Car, in many ways an updated version of the Avto. It wasn’t quite GPS, but instead used an ‘inertial navigation system’, or gyroscope that was sensitive to both rotation and movement. There was nothing portable about it —to receive positional information it needed to be hardwired to a modified car transmission.

The forerunner of the GPS came in 1985, with the Navigator from Etak. It used geocoding, meaning it could reference a street address with a latitude/longitude point. This dallied with a digital compass mounted in the car, and two wheel sensors fitted to the non-driven wheels. But for all its technical prowess, it remained a niche product, shifting only a few thousand units.

Steven Lobbezoo developed the first commercially available satellite navigation system for cars in Germany. Nicknamed ‘Homer’, after a tracking device from James Bond, it was quite the gadget: a modified IBM PC integrated into the glove compartment, a large disk for map data, all displayed on a flat screen. It used dead reckoning—a navigational technique that orients itself with fixed positions, measuring distance and direction traveled from these positions.

At the end of the decade, Japan pushed CD-ROM routing technology. These informed the dead reckoning system inside Toyota’s Crown Royal Saloon G, available only in Japan. Afterwards, fellow countrymen Alpine released their version of CD navigation using GPS satellites. But CDs could only map a limited area, while taking up space in the car. So a few years later, Ford piloted SD cards in their MyFord Touch system.

The ‘90s saw commercial car navigation heat up. Eunos Cosmo became the first production car with a built-in GPS navigation antennae system, which Mazda claimed was accurate to 45 meters. Reviewers at the time remarked that it took just nine seconds for the screen to zoom in, which is as amusing as it is unrelatable.

Mazda may have been the first, but GPS soon became an industry buzz, with several carmakers piling on. Toyota introduced “Electro-Multivision” GPS inside the Toyota Soarer, featuring an attractive 6-inch color LCD screen. Mitsubushi added a GPS system to its 1992 Debonair model, and BMW released the first European model with GPS: the BMW 7 series.

Portability becomes vogue

By the turn of the century, market weight was shifting toward portable navigation devices (PNDs), which allowed consumers to buy road navigation separately from their cars. Amsterdam-based TomTom, originally a B2B applications company, pivoted their focus onto PNDs, and became a household name alongside US company Garmin.

Photo by Brecht Denil on Unsplash

And lo, then came smartphones and apps. Navigation made obvious use of the medium’s bristling technology and inbuilt GPS functions. This era is dominated by web mapping platforms — which have put the world inside people’s pockets. Apps like Bing Maps, Waze and MapQuest fight over the crusts, but this market has one king: Google Maps. In fact, we could basically rename this entire article ‘Navigation Before and After Google Maps’ with perfect utility —even though other apps market themselves as more driver-oriented.

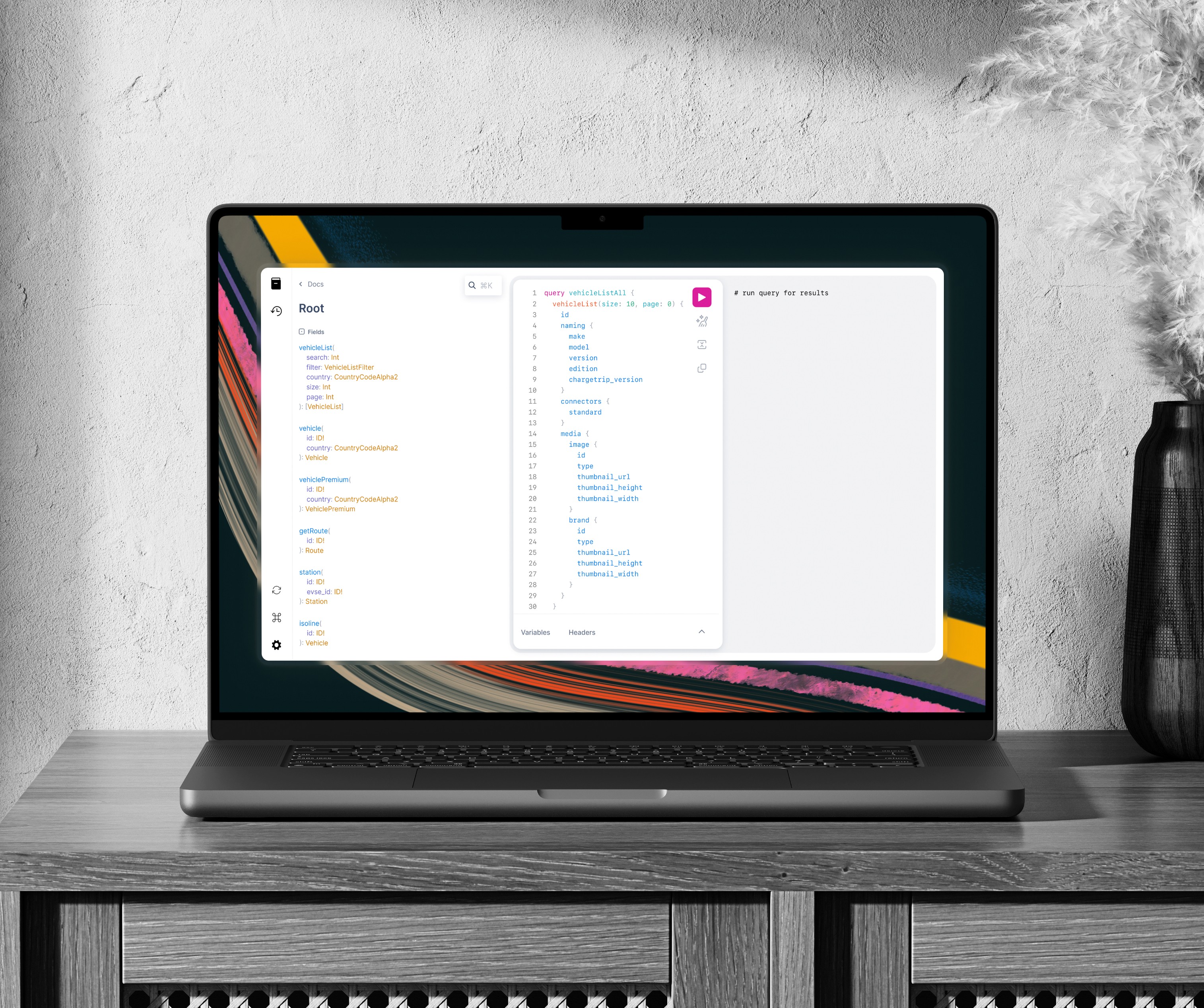

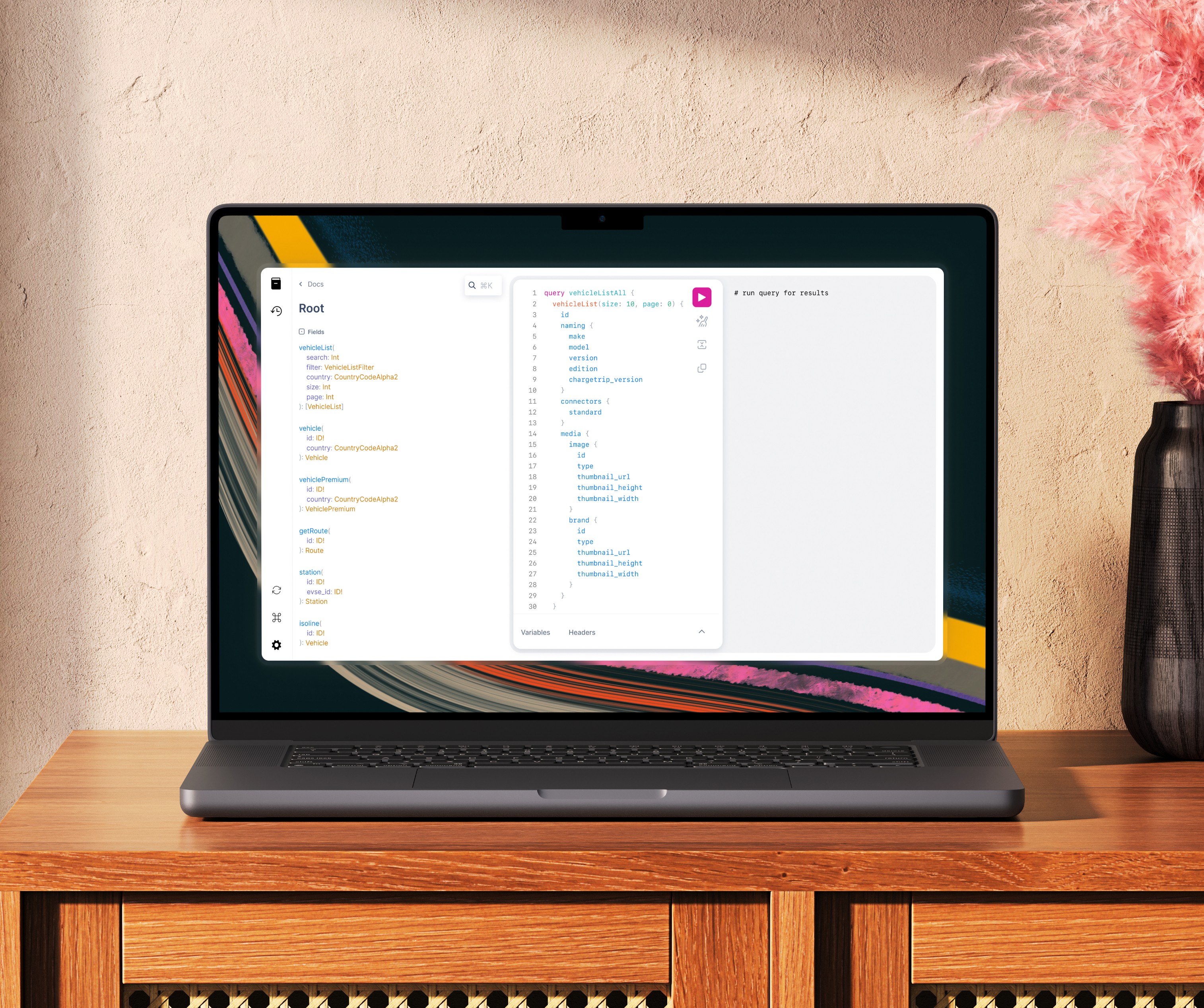

As the car market segments and electrifies, the next step of navigation envisions a system sensitive to the user’s vehicle and driving preferences. Chargetrip, founded in 2017, caters to EVs only. Highly conscious of the range and charge anxieties that vex EV drivers, it tailors routes to the specific variables of a user’s car, as well as environmental factors. Chargetrip is embedded in a broader market shift towards customization, which believes in serving the user as an individual, not as a collective. Other trends point to a 3D HMI experience, where companies like Unity are creating a ‘digital cockpit’ —a new kind of navigation experience ripped straight from an ’80s sci-fi film.

Compass to app, and beyond

From ancient sailors reading a compass instead of the stars, to steampunk contraptions, to systems that understands how and what you drive—navigation has enjoyed a colorful, age-spanning trot into modernity. Future-gazing is a dicey game, but however navigation grows, it will almost certainly become more precise, more detailed and more relevant to the individual user. At Chargetrip, we’re excited to be part of the rising tide of a new generation of in-car navigation.

Learn more about how Chargetrip can improve in-car navigation: